Motto:

„Then Petőfi, a born attacker,

Unruly, but the coach still forces it.

The best age as a striker: twenty-six,

He runs, he hides, he jumps, he feels.”

(from the poem Sport by Balázs Szálinger)

Little is said about the sporting aspects of Sándor Petőfi's life, although there is much to talk about, since the poet, who was born two hundred years ago, was always active. „He is skillful and daring in games,” Gyula Illyés describes the schoolboy Petőfi in his monographic prosaic work. „His slim, slender stature is carried swiftly by his legs; he beats everyone in running races. With his long arms, he throws the ball further than anyone. That is until someone from the children's team starts taunting him for throwing with his left hand - ungainly! From then on, he doesn't throw.” The recollections of contemporaries further color the picture. He liked ball games. He enjoyed sliding on the ice in the winter. He was good at gymnastics, and he wrestled when he had to. His love for exercising is clear from his poem Búcsúzás (Farewell), written in 1838. „And you, dear places, where we have had much fun / Or sat down in a great circle, or whipped the ball / And scampered, or leaped, or in sweet joy / sung to merry melodies, and now there is silence at our favorite / Place, we shall leave you hereby!” (free translations)

However, it is not clear whether he could swim. If we go by his journal called Úti jegyzetek (Travel Notes), the answer is presumably no – he nearly drowned in the Rimava River while walking in Rimavská Sobota in May 1845. „The water is not big, but I was bathing just below the mill, where, wanting to strike straight through, I was swept under the waves. If it had been wine, but to drown in water... it would have been embarrassing!” Or there is the case of a year earlier, shared with the public by his contemporary colleague, cartographer Imre Péchy in 1879. Petőfi was rowing with local acquaintances in Dunavecse that spring when János Szűcs (who was in the boat as a helmsman) fell into the Danube and was almost lost. The poet, however, "managed to snatch him from the jaws of death by steering his boat swiftly. Petőfi was hailed by many for his bravery; only his loving mother warned him not to go on the boat again, for he might fall into the Danube, too." Almost immediately, he made the heroic adventure into a poem (titled Vizen (On water)): 'I talk to my small boat / The chattering foam; / I stretch the paddle, / that I almost sweat. // Mother, if you could see me now, / I know you'd say: / „For God's sake... if you fall... / Aren't you afraid to die?” (free translations)

„IS HIS BOAT HEADING ITS DESTINATION?”

The „prepositional tension” lurking in the first two verses illustrates the difference between being on the water and being in the water for Petőfi – who not only loved rowing but understood it as well. As Péchy points out in his aforementioned article, “our poet, moreover, perfected rowing to such an extent that he could steer the boat – with two paddles – without a helmsman.” Even if he did have a helmsman, he sometimes interfered with his work, and on such occasions, he quipped: „in order to paddle the water, you also have to worry about whether your boat is headed to its destination.” (free translations)

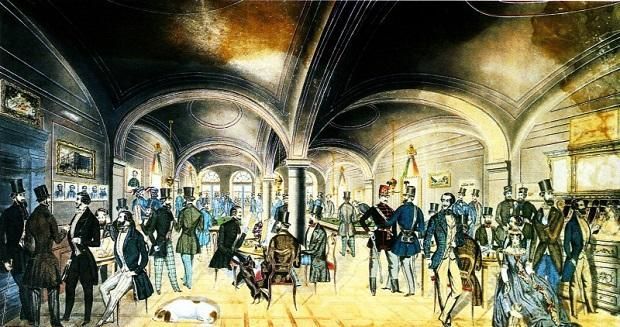

Of course, Sándor Petőfi's 26 years included many other sporting activities. He traveled almost the entire country on foot, often because he had no other choice, but he also enjoyed wandering in nature for pleasure. He also enjoyed playing cards, dice, and pool, mostly at Pilvax, where the balls rolled on four – to use the parlance of the time – „bowling tables.” Whether he was a good player or not is hard to say: some recollections say that he was good with the cue, but Márta Szabó, in her study Biliárd és szerencsejátékok a kávéházban (Pool and Gambling in the café), writes that „he loved the game, but he could hardly play pool. On one occasion, he got into a fight because he had thrown a ball into another guest's glass.” (free translations)

Petőfi, like Mór Jókai, used his own cue in Pilvax; the light brown, smoothly polished, tapering downwards, inlaid piece is on display in the Petőfi Literary Museum.

As well as his chess set because Petőfi was also fond of this popular intellectual sport. A Pesti Hírlap article published in 1908 recalls an incident when the poet stayed with the Tyroler family in a small courtyard room in Pest. "Old Tyroler was a passionate chess player and after dinner, in the evening, he would play chess for hours with the poet, who would laugh with gusto at Uncle Tyroler's Hungarian pronunciation when he could not articulate the name Petőfi and kept calling him Péterfi.” Petőfi did not, however, use any chess terminology in his writings, except in the first lines of his short story A szökevények (The Runaways), published in 1845, and in his letter to János Arany, written on July 1, 1848, in which Petőfi wrote: „But do not grieve, that was the end of your enemies, with which they carried me off, that was their end, one more tap on the head, and then checkmate!” (free translations)

„IF YOU GET A BULLET IN THE HEAD, LET ME KNOW!”

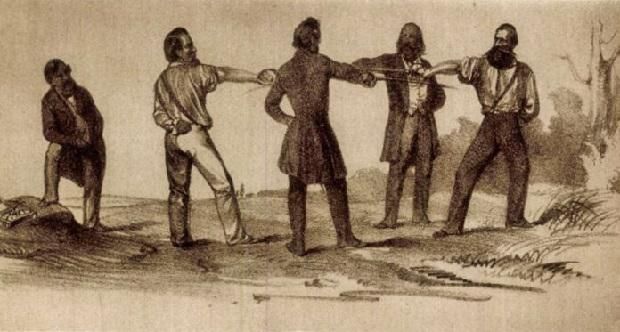

Earlier, in our video series „Budapest Football Tales,” we mentioned that Sándor Petőfi applied for military service in the very building on Akadémia utca in Pest in 1848, where the Hungarian Football Association was then founded in 1901. The gun-toting poet's more immediate sporting connection is that he tried fencing and shooting in one way or another. From an article published in Új Idők (New Times) in 1949 by the eminent sports historian Ferenc Mező, we know that the young man from Kiskőrös learned swordsmanship from the master of the National Fencing Institute in Pest, Lajos Chappon, author of the 1839 textbook Theoretical and Practical Introduction to the Art of Fencing. He attended the fencing school at the instigation of his friend, law student Antal Várady, whom he met in 1843, and he was his companion during most of the lessons. According to the occasional opponent's memoirs, Petőfi found it hard to take being cornered, and as a „sensitive” man, his self-esteem was hurt by such situations, and his skill in fencing and target shooting made him capable of settling disputes in a chivalrous manner. In a poem entitled Levél Várady Antalhoz (Letter to Antal Várady), written on May 22, 1846, he inquired about the recent adventure of a fellow fencing student: „Has the duel happened? and are you still alive? / If you get a bullet in the head, let me know / Write to me right away so that I can rush to Pest, / And take revenge for you, my friend... / A word is a word, but I really don't like / That you're ready to risk your life / for any foolishness. / Do you think your body and soul are beard? And if / they shave you down, will you grow out again?” (free translations)

Although we know of several documented examples of duel-threatening situations in Petőfi's life, in the end, there is no evidence that such a drastic release of tension ever took place. In the 1973 issue of the journal Tudományos Sportélet (Scientific Sports Life), we read the most detailed collection on the subject by László Varga, right from the first episode with a classic writer in the role of the duel assistant (and narrator): the source of the story is Mór Jókai. „Once Petőfi enters with great strides. ‘Will you be my duel partner?’ ‘Of course, I do. Who hurt you? Who do I challenge?’ ‘Benőfi!’ ‘And for what reason?’ ‘Because he made assonance of my name. How dare he make a name like mine for himself?’ ‘That's not enough reason for a duel.’ ‘Yes, but he writes bad poetry, and the public thinks I wrote it all.’” He was terribly angry with him: but then he had to give up the idea of the duel: after it turned out that his assonance was an ordinand at the Seminary of Eger.” (free translations)

The half-century-old article warns that not everything in Jókai's soaringly imaginative anecdotes should be taken literally, "but in this case we must give credence to his description, knowing Petőfi's sudden, unruly dueling skills." This sudden dueling skill was also evident in the poet's later moments of fiery heat. For example, in 1845, when he had a disagreement with Mihály Tompa, to such an extent that, according to his poet companion, after they met, "a few weeks later, things were about to go to gunfights between us." He also challenged newspaper editor Imre Vahot to a duel for publishing one of his poems without his permission, but the challenged party backed down after a day and a half of deliberation. Petőfi complained about the cowardly retreat in a letter he wrote to János Arany. He later sought a duel with the lawyer-editor, still in vain, although, according to Gustáv Zerffi, he practiced regularly in the courtyard of Neugebäude under the command of Captain Mack in preparation for one of the affairs.

„I NEVER FIGHT FOR FAME ALONE”

His most famous "almost-duel" is connected to the 1848 election of the senator of Szabadszállás. The poet who was ultimately defeated in the election challenged his victorious opponent, Károly Nagy, for his personal and impertinent article in Pesti Hírlap. "When I first sent my seconds (my duel assistants, Jókai and Pálffy) to him, not only did he not accept the duel outright, but he immediately ran to Móric Perczel, as chief of police, to protect his life, because I wanted to take revenge on him by illegal means" - Petőfi recounted the events. The other candidate for senator reluctantly but finally agreed to a duel on the sword, but the challenger insisted on the sharp, pistol-fought version. "My principle is that I never fight for fame alone; but if I do, it must be to the death, because duels are no joke; I will only fight with the man who insults me like that cripple so that I can then brandish my weapon at him with the same passion as a mad dog coming towards me." (free translations)

Petőfi was not afraid of a dueling threat, even when he had business with his superior. On May 8, 1849, he wrote to Lieutenant General György Klapka (the affair gave birth to the poem “Egy goromba tábornokhoz (To a Rude General)”, after the ad hoc Minister of War had failed to confirm him in his rank of major during their tense meeting in Debrecen: "You 1) did not consider my word of honor in certain matters sufficient. You 2) assumed that I wear the major's uniform without being appointed. You 3) only wanted to release me against a medical certificate. You 4) forbade me to write. All this briefly: 1. Petőfi is not an honest man. 2. Petőfi is a cheeky and vain deceiver of the world. 3. Petőfi is a bad patriot because he leaves the battlefield and lies about illness. 4. You are Petőfi's totalitarian leader, as the Habsburgs were the nation's totalitarian leaders, who subjected him to censorship. Sir! These are things for which, in peaceful times, I would have called you for revenge, and perhaps I would have shot you like a sparrow, for I shoot fairly; but now, since we have to fight not ourselves but the enemy, I have chosen the second way, which my patriotism has prompted me to do, and have left, in silence and modesty, an army whose minister does not believe in the word of honor of his own officers, whereas the word of honor of captured Schwarz Gelb officers is also valid.„ (free translations)

(The article appeared in the Saturday supplement of Nemzeti Sport, in the January 14, 2023 issue of the magazine Képes Sport.)

translated by/fordította: Vanda Orosz

A világ legjobb hatosa? – a Ryan Gravenberch-portré